An indispensable guide

October 30, 2018 · Insights

Communities find direction, will of the people through long-range planning

By Brandon Bias, AICP, LEED Green Associate

Today’s comprehensive long-range plans are not strictly limited to the large municipality equipped with an army of planners and a sizeable budget. On the contrary, they are proving just as valuable to small towns and counties across the country, as each seek to steer their community toward a vision that is a better match to core principles, needs and wants.

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, comprehensive plans were simpler and less inclusive, and would merely identify a number of tasks to accomplish over a designated time period. Today, they are more flexible documents that establish parameters for future decision making even as factors change. Placing the focus upon a strong vision and set of principles provides a community with the ability to alter or adapt the plan when specific recommendations may no longer be relevant.

As a more recent trend, communities of all sizes have turned to long-range plans to more succinctly define a sense of place. Parks and public spaces are key locations for making that happen. Jefferson County and Birmingham, for example, had a unique opportunity to improve community health through a master plan that includes trails, bike lanes, sidewalks and greenways. Since the Red Rock Ridge and Valley Trail Plan’s creation and adoption in 2012, with the assistance of GMC, nearly 60 miles of the park system have been completed.

While no comprehensive long-range plan can be pigeonholed into a particular template, most communities have one thing in common – limited financial resources. Therefore, goals are often tempered by financial realities. In the end, the plan is meant to guide a community through a series of choices over a designated period, helping it realize its vision and follow its principles.

The Process

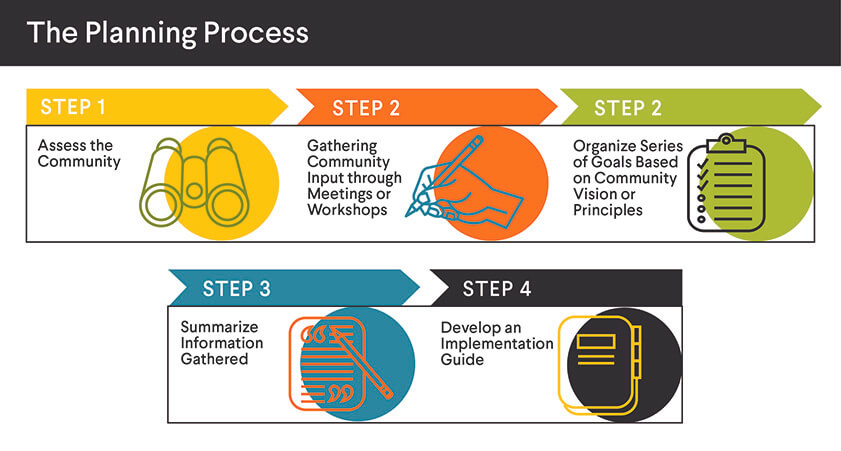

No matter the intent of the plan or size of the client, planners take the critical first step of assessing current conditions by researching demographics, land use, prior city growth, transportation infrastructure, community facilities, current services and a host of other factors.

In the process, they search for areas in need of improvement, as well as reasons for improvements in other areas – in other words, why one neighborhood has been more successful than another. Planners examine previous plans to determine how successful, or unsuccessful, they’ve been, and in the process create a reliable snapshot of the community.

Beginning at this stage and throughout the process, participation and involvement is essential. It is recommended that a steering or advisory committee comprised of key stakeholders in the community be used to facilitate the process. Generally, these participants are engaged in the day-to-day business of the community. Along the way, planners ask some key questions – Is this right? Is something missing? Did we spend too much time on something that is not significant?

The next planning step is community engagement. GMC planners meet with citizens in the community across all geographies and demographics to gain a better understanding of who they are, who they think they are and who they think they want to be in the future. They subsequently record information that is later distilled to create a vision for the community, define community principles and determine important recommendations for the future.

The process begins with a general community meeting, or community workshop, where participants are assigned to small groups in order to facilitate conversations on various topics. During these exercises, planners utilize a large map to identify weak and strong areas in the community. Fundamentally, they want to understand the participants’ vision of the future with a series of “foot in the door” questions – Why do they want to do these things? What do they want to improve?

Along the way, the preconceived notions of both planners and city leaders are put to the test. For example, a community center in the middle of a low-income neighborhood might be considered a strength by city leaders, but a poorly maintained eyesore by its residents. This is an important aspect of the community engagement process to challenge expectations with the realities “on the ground.” As a result, planners hope to understand as many dynamics of the community as possible to better plan for the future.

Next, planners organize a series of goals around various planning elements. These can address land use, transportation, community facilities and services, housing, economic development, etc., and are calibrated on a community-by-community basis. Citizens and the advisory committee are engaged at different following stages to ensure the planners have not veered away from the community vision or principles.

Planners then summarize the information into a succinct final comprehensive plan document. The quality and appearance of the final document is an important part of the process, since it will likely be used as a marketing tool to attract potential investment.

Discovering the Will of the People in Brewton, Alabama:

For the small town of Brewton, Alabama – population 5,500 – the overriding goal in developing its back-to-back five-year plans was to seek out and execute the will of the people. Mayor “Yank” Lovelace, a business owner with a penchant for planning, says the process brought a lot of new ideas to the table as well as helped achieve certain gains, such as attracting the 300-employee IT company, Provalus, to the town in 2017.

Lovelace says the dual long-range plans provided an operative way for him to do his job. “If the people say that’s what they want and I’m working that plan, then I’m doing what I was elected to do,” he says.

Multiple open forums held at the beginning of the process proved to be an eye-opening experience. “We started to notice a pattern. At the end, we had developed a fairly comprehensive plan. For a mayor and city council, that gives us the authority to go forth and work on those problems.” Putting the projects from the first five-year plan on white boards enabled the city to track its accomplishments, and even finish most of the projects within four years.

When tackling the city’s second five-year plan shortly after his re-election in 2016, the planning team chose to engage more of the community. “We held two or three public hearings at City Hall, then set up public meetings in each district and made the councilmen responsible for getting people to attend. That way we received more input and more people were involved in the process.”

At the end of the hearings, an initial draft of the plan was created. “We said, ‘OK, here are all the items that you’re saying you want. Which of these items are more important?’” From there, it went to the planning board and the city council for approval.

If there is one common denominator in the Brewton plan, it is that that all the projects seek to improve quality of life, whether through street improvements, parks, rodeo arena, landscaping or Christmas displays. “Quality of life includes your schools, your roads, your activities,” Lovelace says. “We now have a full-time program manager that does nothing but schedule events, such as music or kite flying on the day before Easter. We try to have something every weekend. During Christmas, our sales tax went up 10 percent as people came out to see all the lights we’ve got up.” Another offshoot of the plan was the creation of a natural gas district, which has become a vital funding mechanism for the city.

With so many changes, the rest of the state and country are beginning to take notice. In fact, the city has been ranked nationally by various groups for its favorable living environment. “The State of Alabama and the governor all went crazy over the fact that a little town like Brewton could get a computer tech company,” Lovelace says. “That’s a huge deal. Site selectors are looking for reasons to check you off the list, not for reasons to put you on it.” Undoubtedly, the city’s commitment to long-range planning, developed with the assistance of GMC, has been a contributing factor to its success.

Mobile, Alabama Transforms Itself

Earlier this decade, Mobile, Alabama was facing a number of challenges, including limited mobility, sprawling conditions and declining neighborhoods. The city was continually losing population to both the west and east, a consequence of not having taken an introspective look at itself or its goals in nearly 50 years.

Shayla Beaco, executive director of Build Mobile, says the city was at a pivotal point. When its new mayor – Sandy Stimpson – took office in 2013, community leaders urged him to spearhead the creation of a long-range plan for the city.

The “Map for Mobile” is a shining example of how a long-range plan can literally transform a municipality’s future. As such, Mobile’s comprehensive plan lays out an exciting vision for the city’s long-term preservation, revitalization and growth. The core values that guide the plan, defined through a robust public process, include a stronger, mixed-use downtown, supported by diverse and connected neighborhoods, businesses and open spaces. Most importantly, the plan includes realizable action steps to ensure that recommendations become reality.

“Because we’d gone so long without a plan, we really wanted to tie our city initiatives to a planning process,” Beaco says. “Our mayor asked that it be the type of plan that we could utilize on a regular basis and had measurables associated with it. That way we could provide citizens with a sense of accountability.”

The plan’s early success can be attributed to one factor – Mobile did a stellar job in facilitating community engagement. The first public meeting far exceeded expectations when more than 600 people showed up. “Being a new administration, it was important to ensure that all Mobilians were given an opportunity to be heard,” Beaco says. “We needed to make sure that all of the underserved areas of our city were at the table at the front end of the process.”

Encouraged by the level of participation, the team realized that it needed to conduct additional neighborhood outreach efforts to more effectively target individualized needs. Ultimately, more than 50 neighborhood meetings were held over a year’s time. “The common theme that we started to hear was that people wanted a greater emphasis on connectivity; they wanted to be able to utilize the pedestrian amenities that are symptomatic of good, strong neighborhoods,” Beaco says. “People wanted to walk to school, walk to the corner grocery, and walk to their neighbor’s houses in a safe and secure way.”

“They also wanted to leverage our 300-year-old city’s historic character to maintain a sense of identity throughout our neighborhoods. The conversation began to focus on ways to protect the design qualities of these neighborhoods.” Additionally, citizens wanted an environment that encouraged commercial development opportunities and enhanced quality of life. That meant re-zoning certain areas to boost investment potential.

The city initiated the plan’s first phase by laying out its “vision” in November 2015, receiving a unanimous vote of approval from the Planning Commission. “We started out at 10,000 feet; now we’re slowly starting to land this plane,” Beaco says. “The next step for us was to introduce our general land use plan and major thoroughfare plan. Those two documents were adopted in 2016, and we are now toward the end of our zoning overhaul.”

Beaco says the plan is meant to be a living document that can adapt in response to changing market dynamics, demographics and needs. “This plan continues to live on. It has benchmarks within it that help us to know where we need to start and finish a new effort, but it’s going to run, in our minds, for the life span of our city process.”

Indeed, that is the essence of a dependable long-range plan. It is not merely a list of projects to check off a list, but is instead a flexible, malleable document that ultimately becomes a reflection of the very community it represents.