Reimagining park experiences through the eyes of millennials

Millennials. Whether you realize it or not, your life is affected by them. This generation of young people born between 1980 and 2000 is gaining prominence and significantly impacting the world. They are changing the way we buy and sell goods and services, interact with one another, and how we plan and relate to the built environment. The business world has been aware of them for a while now. Likewise, publicly-owned park systems need to recognize millennials as a force to be reckoned with and tap into the opportunity they bring. To do this, park systems must identify and understand millennials and what they are like.

Studies and surveys show that millennials place a higher value on experiences than on possessions. Thrill-seeking millennials have spawned a new travel industry, known as adventure tourism, where tourists exert themselves, connect with nature, and take on an element of risk. They snap selfies on their smartphones and post the images on social media sites like Instagram so their friends can see where they are and what they’re experiencing.

Public parks already offer the adventures and one-of-a-kind experiences millennials are seeking around the globe. What if parks could understand and curate their overall experiences and motivate millennials driven by FOMO (fear of missing out) and YOLO (you only live once) to partake in local adventures? Could public parks spawn a new generation of park enthusiasts?

Better yet, if public owners invested in their parks with an eye toward generating revenue, catering to millennials could pave the way for public park systems to recoup operating costs and provide funds to fulfill their missions to protect and preserve natural and cultural resources. As budgets get tighter and park systems work to secure and maintain adequate funding, adventure tourism presents a huge opportunity that should be seized.

The time is right to reimagine park experiences through the eyes of millennials.

Here come the millennials

Most definitions describe millennials as those presently between 17 and 37 years of age. They are the largest generation ever, with 92 million people in the U.S. alone. They are also the most connected generation, with smartphone ownership approaching 100% among those ages 18 to 34. Millennials have been raised with an abundance of technology and material possessions. This has led to a generation that places more value on experiences than things. A 2014 Harris Poll funded by Eventbrite reveals that more than 3 out of 4 millennials (78%) would choose to spend money on a desirable experience over buying something desirable. As summarized by Eventbrite:

[T]his generation not only highly values experiences, but they are increasingly spending time and money on them. . . . For this group, happiness isn’t as focused on possessions or career status. Living a meaningful, happy life is about creating, sharing and capturing memories earned through experiences that span the spectrum of life’s opportunities.

David Butler, owner of WTG Talent Solutions, helps companies understand what makes millennials tick and how to relate to their particularities. He confirms the results of the Harris poll. “Millennials are way more interested in what they do rather than what they have.”

Butler describes millennials as driven, but not in the same way as their “yuppie” parents. “Millennials are competitive,” Butler says, “but not about acquiring things. It’s ‘what am I doing compared to what you’re doing?’ They like attention and they share that through social media.”

More than previous generations, millennials are dedicated to wellness and devote time and money to an active lifestyle that includes eating healthy, exercising, and spending time outdoors.

Perhaps most significant in regards to the future of public parks, millennials are less interested in observing from a distance. Rather, they crave connection and authenticity, and they gravitate toward participatory experiences. They then share them with others and influence decisions. One study found that 92% of millennials share their travel experiences on social media and that one in three people book a vacation after falling in love with a hotel or destination on Instagram.

The time is now

As a group, their spending power is enormous. According to recent studies, millennials in the U.S. wield about $1.5 trillion in annual buying power. With the oldest millennials just now reaching full steam as far as earning potential, that number is expected to reach $3.39 trillion by 2018 – the most spending power of any generation ever.

“When you look at the millennials’ disposable income, they are the future,” says Butler.

A significant chunk of their income is spent on experiences such as adventure tourism, which is a $270 billion worldwide industry. This market grew by 65% between 2009 and 2012 and is still growing.

Patrick Neuber, an architect with Goodwyn Mills Cawood, says the opportunity is now. “If public parks focused on capturing the imagination of millennials, they could garner a share of their spending power and bring in greater revenues through fees for lodging, campsites, dining and other park experiences.”

“This is not to suggest that public parks start focusing on making a profit,” he explains, “but an increase in revenue could free them to accomplish their bigger missions to protect natural and cultural resources and provide affordable access to those natural resources and build resilient communities around them.”

The Indiana state parks system, for example, is approximately 70% self-funded through access fees, hotel lodging fees, and retail and restaurant sales. This high return on investment provides more opportunity to achieve their broader goals of environmental restoration, management of natural, cultural, and wildlife resources, and land acquisition, all the while having a smaller impact on the state budget.

How do we get there?

To tap into the millennial market, public park systems must acknowledge their position in the experience business, and then begin crafting and curating these experiences for the new generation. This step needs to be taken before building new lodges or adding amenities.

“If park systems are going to respond to millennials, they must first identify what’s important to the next generation of park users,” says Neuber. “They should ask what this looks like for the parks. They must decide a course for the future and analyze where they currently sit in the marketplace. Then a response has to be planned and realized.”

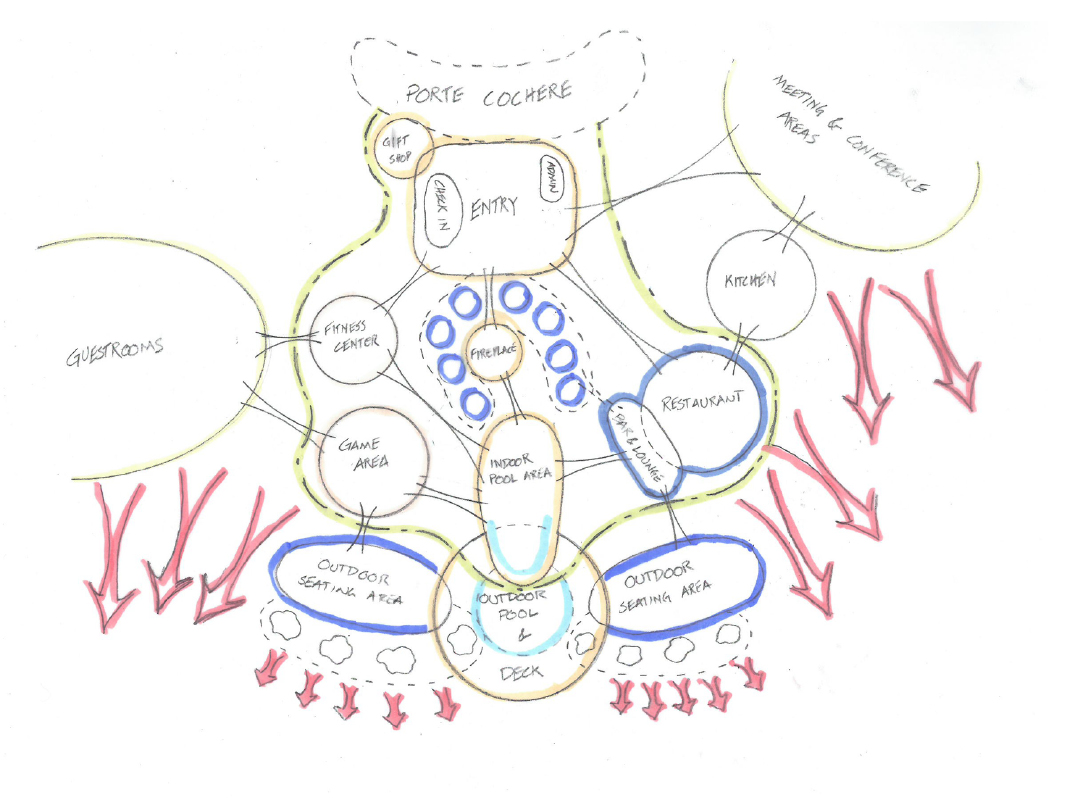

In many cases, says Neuber, public park systems will need to upgrade or replace their built assets to curate the type of experience that will draw millennials. Public parks need to offer competitive amenities and comparable services that showcase their unique characteristics. This could mean offering a full-service hotel or other hospitality experience that relates to the individual characteristics of a place.

However, public parks do not necessarily need to out-spend the private market since their offering of adventure and connection to nature is considered extremely valuable to millennials. In some cases, rebranding and reprogramming what is already available will attract millennials searching for exciting, participatory experiences.

The State of Tennessee recently began a process to revitalize its park system to address downward trends in key areas such as overnight stays at park lodges. They started with experiential mapping of all of the parks and reviewing the competitive experiences. This led to the replacement or major renovation of a majority of park inns.

Brock Hill, Deputy Commissioner of the Bureau of Parks and Conservation for the State of Tennessee, remarks, “Every park in our 56-park system has a unique story to tell. Focusing on and identifying a core theme around each story is the foundation of all that follows in developing experiences for our visitors.”

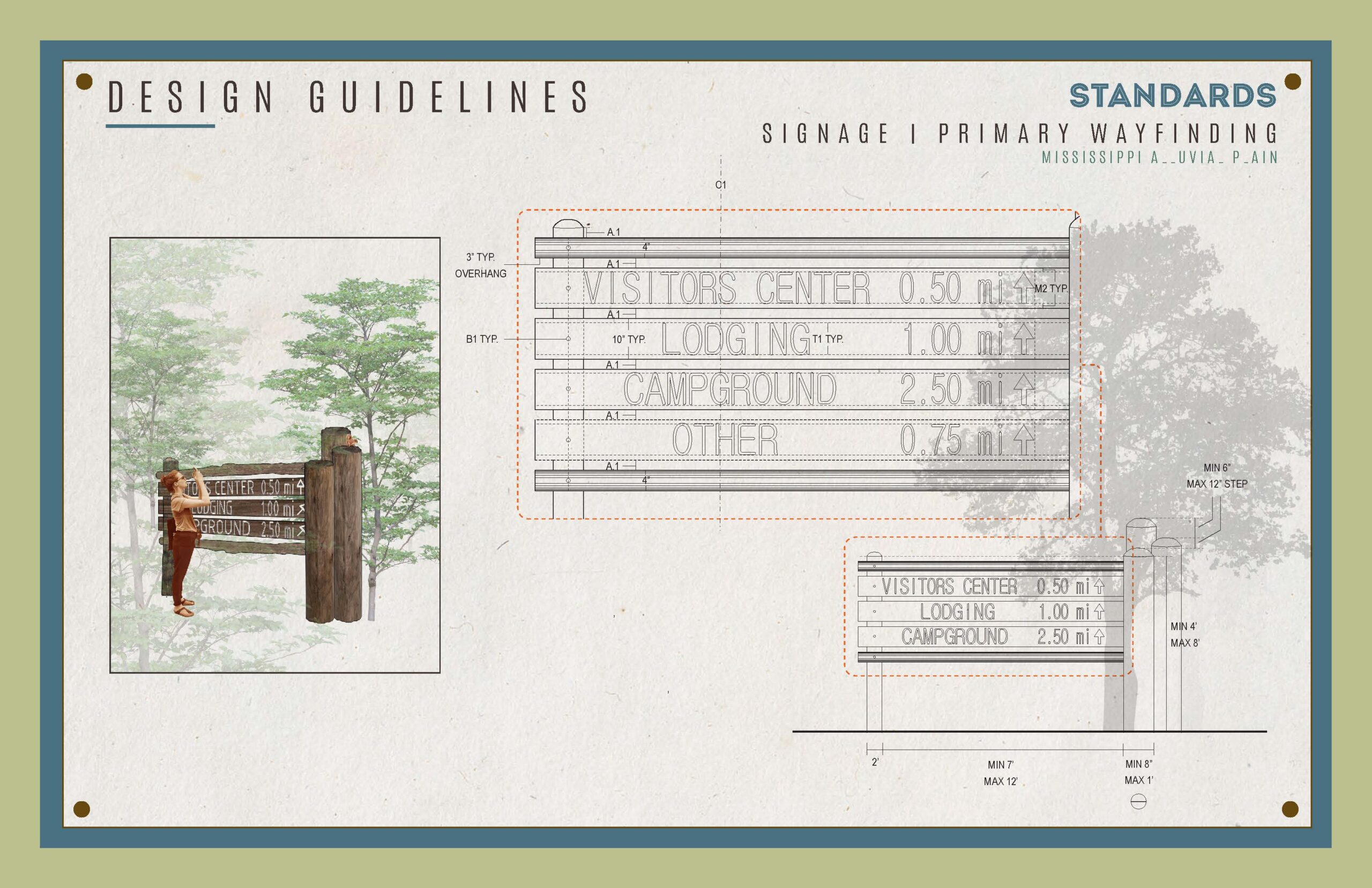

As part of this process, the State of Tennessee hired GMC to help identify and enhance the visitor experience at several state parks through facility studies, lodging studies, planning and programming, and development of design guidelines for the entire state park system.

As GMC’s project manager for the Tennessee State Parks planning work, Neuber says, “The purpose of the studies was to analyze the market to determine what amenities the market could support that would be desirable to potential visitors, such as millennials.”

The studies yielded recommendations for new or upgraded lodging and restaurants “built in a sophisticated, yet relaxed contemporary style that is comfortable and connects guests to the natural surroundings and each other. The projects have to create a unique sense of place.” The focus of the recommendations was to create spaces where people could interact with each other in a unique and natural environment that offers a diversity of experiences within the park.

Neuber is also leading the development of design guidelines. These guidelines will foster a unity of design among the parks without diminishing the individuality of each one. The guidelines will help create a brand and identity for the park system so visitors will know they’ve arrived in a Tennessee park while creating an environment where guests are encouraged to explore each park’s unique characteristics.

Don’t just throw money at the problem

While new lodges or amenities could be part of the solution to preparing for the next generation of park users, there are less costly options that can still pay big dividends.

“Start by understanding what you have, what the market says you may be able to support, and finally, what you need,” says Neuber. “Then find out what appeals to millennials and craft an experience with the proper amenities to appeal to them. It doesn’t have to take a lot of money. Rebranding can be a big part of it.”

“For example, say you have a park with two distinct user groups like horseback riders and bicyclists. Normally those are seen as conflicting uses, but what if we looked at them from the perspective of experiences sought by the two groups?”

Neuber explains, “Look at commonalities as well as differences between bikers and horseback riders. There are functional items that both groups need, like community engagement. You can explore ways to build common facilities and features where scheduling can separate the uses while sharing the facilities.”

Neuber calls this “experienced-focused thinking.” He adds, “Instead of saying every park needs to be the same, we’re looking at each park and the type of experiences it offers and how we are spreading these experiences across the system. In some cases, we are asking whether the current park is offering the right experience and what the market is lacking.”

Although the main focus is not generating a profit, revenue and funding are still significant issues that cannot be ignored, Neuber adds. “It’s still important to identify the revenue-generating experiences and to ask how can we get money to help us fund our objectives?”

Lodges, inns, cabins, and campgrounds generate significant revenue in parks without usage fees, and investing in them has the potential to pay dividends. However, these amenities should no longer be considered just a place to stay while visiting a park. Instead they should be viewed as the first step in crafting an experience.

Lodges, inns, cabins, and campgrounds generate significant revenue in parks without usage fees, and investing in them has the potential to pay dividends. However, these amenities should no longer be considered just a place to stay while visiting a park. Instead they should be viewed as the first step in crafting an experience.

Lodging at parks should offer millennials an authentic and personalized experience. Current trends are moving toward shorter stays, innovative uses of technology, and unique perks such as finding ways to connect people to the region or local community through food and beverage.

Millennials’ dining preferences differ as well. To appeal to this group, parks should move away from buffets to “quick dine” and plated service restaurants, with an emphasis on locally-sourced food and beverages. “Creative and local are better than comfortable and expected,” Neuber says.

Getting buy-in

New lodges, restaurants and cabins are expensive and require large capital investments. This could be in the form of budget line items, bonds, or even public-private partnerships.

Regardless of the funding arrangement, the buck stops at the ruling body. For state-owned parks, that means the legislature. It is vitally important that elected officials are on board.

“If you want to change the way your parks are marketed, if you’re wanting to spend money on things like market-competitive lodging and restaurants, you’ll need to talk to your legislators about millennials,” says Neuber. “It’s about marketing, branding and contemporary design, but it has to function within the political climate, and making a business case is key.”

Deputy Commissioner Hill confirms the importance of gaining legislative support, as well as clearly communicating the vision. “Having support from your legislature for funding needs is a given,” he says. “However, working to make a park experience better may involve changes that meet resistance from some park users. Communicating these efforts to your legislators prior to implementation is very important.”

“When you make changes to what a park provides or build new features based on attracting new visitors, you will inevitably meet resistance from someone,” Neuber says, “but communicating the bigger vision—a healthier and more vibrant park system with long-term positive economic support—can help alleviate concerns.”

Conclusion

The last great push for park development in our country was in the 1930s with Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration – long before the millennial generation came to be. Since then, there have been sporadic building and development programs, but nothing comparable to that era.

We are now on the cusp of a new wave of development that could be as significant as the New Deal projects, with the opportunity to produce a similar outcome: great natural experiences for residents while preserving our natural resources.

The question is, will public park systems seize this opportunity? Those that do will not only tap into the enormous spending power of millennials, but also engage this coalition of changemakers by offering unique experiences that are, for the most part, out of reach for the private market. The time is now to capitalize on this influential group of adventure tourists and create a new generation of public park advocates. The result will be parks that are prepared to protect and preserve our cultural and natural resources for the coming generations.